Chip Delany described it best, years ago, in an essay titled About 5750 words.

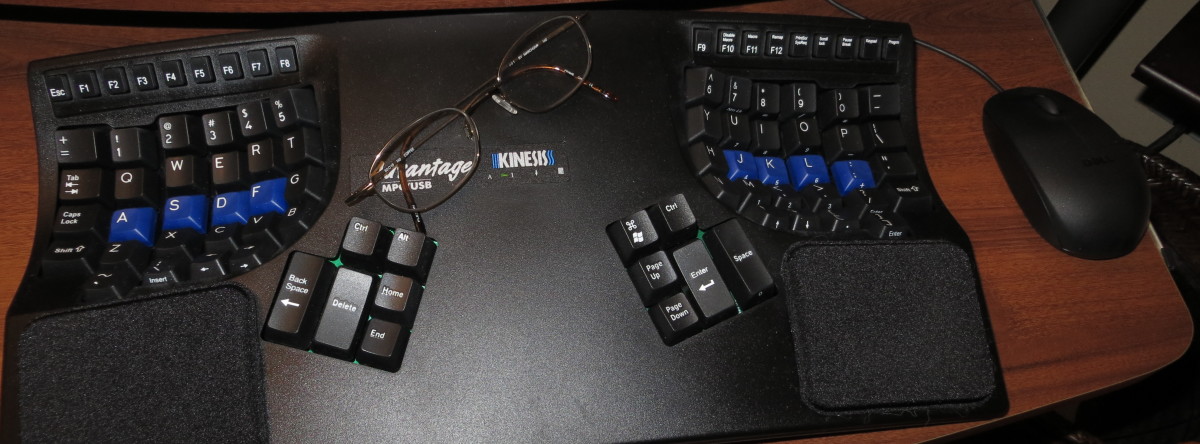

When we think up a story, it seems to be of a certain shape, and we assume that will be the final shape. But then we sit down to the keyboard and write the first word down. *Splat*. There it is. And that first word has now limited our possibilities for the next word. Simply said, if we start by writing ‘The’, then we can’t very well go on with ‘I’ve been dwelling . . . ‘. Our choices are limited. Of course we can erase ‘The’, but then we are back with a blank screen. Or piece of paper. Whatever. Somewhere along the line, we must write the first word.

And the next word has to fit in with the first word, or we’re not communicating. So it begins. The story-shape in the head often winds up bearing little resemblance to the words on the final document.

But there has been a change since that great essay of Delany’s appeared. I discovered it myself the last time I read a piece of a novel for a convention audience. Spiffy new processors, such as Word 2016, which is what I’m using to write this, make it possible to dart blithely into our story, inserting foreshadowing as needed, or making global changes. And the piece of story I read aloud in practice, to my embarrassment, didn’t flow as well as I thought it did. So on the floor I found myself winging it. Not keeping to the document’s phrasing at all.

Because one word did NOT imply the next. Not always.

I think that is becoming more and more common with writers of fiction today. I have tried to read aloud what I find on the page of many new books in my own library, and it doesn’t sound like anything anyone might have said, or written, a generation ago. Possibly this is not important for expository prose, (although I’ve read some journalism in the past few years that is almost gibberish. And from sources that used to be proud of the quality of their journalism.) But it is everything for a writer of stories.

So I’ve taken to the idea of reading, or at least subvocalizing, anything I send out. Whether to a collaborator, an editor or even a friend. And I find myself making changes. Lots of changes. So that one word implies the next and the story keeps working as a story. When read aloud.

And even when the reader is in private, reading words on a page or on a glowing screen, I think that reader, somewhere in the mind, will be able to tell the difference.

Thank you, Samuel R. Delany.