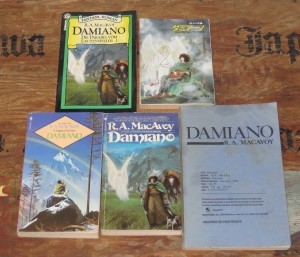

Available Through This Source

When Bantam allowed me to publish TEA, it was with the provision that I would then write a book which would be more worth publishing by them: that it would be solidly in a ‘genre’. I didn’t know exactly what a genre was, but had read a lot of SF. I repeat – I had read a LOT of SF – over the years, and was very willing to do whatever they asked in order to get another book published. After all, I had been told this first tiny book was merely a ‘foot in the door’ and I ought to be very grateful.

Grateful I was, and when advised by my first editor (and at the time I thought that ‘advised’ meant being told from on high) that the next book ought to be something called Sword and Sorcery, because that was what was selling at the moment, I didn’t think of disobeying.

I researched the term Sword and Sorcery, and it seemed to mean the sort of book that had been influenced by Tolkien. There were a great number of those at the time. THE LORD OF THE RINGS trilogy had broken open my heart a number of times. I was reading his books about once a year. The others -the ones inspired by Tolkien – not so much. But I was willing to write as told. No. I was not willing. I was desperate.

But it wasn’t as easy to work from a model as I had expected. I walked around the streets of Palo Alto, CA, and thought about it, waiting for a story to open within me that would be Sword and Sorcery. I started to sweat, because nothing was happening, and I had promised Bantam a book.

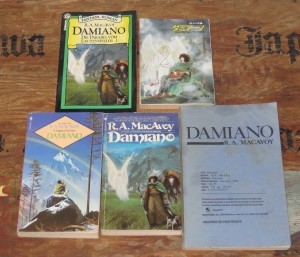

Then one day I walked past a record shop window and there was an album cover on display. The album was called Number 2, by Pierre Bensussan. I’d never heard of him, but the picture on the cover, which was of a young man with a guitar, asleep on a medieval-seeming dining chair, while an obvious king in robes pulled a beautiful woman aside with a hushing finger to his lips – was so simple and lovely and fairy-tale-like that I started imagining things right there on the street. I even went in and bought the album, so I could look at the picture some more.

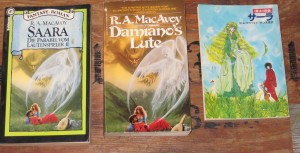

The music inside was astonishingly good and wakened all my stalled imagination. And at the same time this was going on, I was reading a book about the fourteenth century in Europe. I don’t remember if I picked up that book with an eye toward Sword and Sorcery or simply because it was a good book, but between the two influences, Bensussan’s music and the story of the tumultuous fourteenth century in Europe, DAMIANO was born.

I became frantically careful that I got my facts in order about the place called Savoy as it was at the time I had chosen. It seemed to me then, and still seems to me, that when one writes a story containing an impossibility, such as magic, everything else in the story ought to be very realistic, to create a Suspension of Disbelief Bridge upon which the reader can travel, without worry he’s going to plummet out of the story entirely.

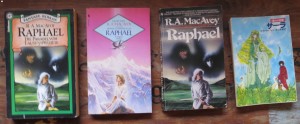

I was told DAMIANO was a failure as a Sword and Sorcery novel, though I had done my best to follow the rules as I thought they were written. It was not a popular failure, it was simply another genre-breaker. I think I’ve written nothing except genre-breakers, benders or simply genre ignorers throughout the years. I’ve never done it on purpose.

The music flowing in my head as I wrote the book wasn’t even medieval, but I consoled myself with the thought that we don’t really know what that music did sound like. Since it was written by young people, it must have had a lot more force and heart than what is now played, so formally, as Early Music. When people didn’t live so long, surely they had to live it up a bit.

DAMIANO is perhaps the most sentimental book I’ve yet written. That, again, seemed to go with the time and place. If one’s life is likely to be short, one’s feelings are likely to be long. I got a lot of letters into my mailbox after writing DAMIANO: some of them I still remember. Some of the people I still know. I got mail from Catholic Sisters. That was an enormous surprise. I’d never thought of the sisterhood as the sort of place where people wrote fan letters. I’ve learned a lot since.

I also learned another thing. You don’t ever, ever kill the dog in a novel. The hero, possibly. Other people, most certainly. But not the dog. I got at least one death threat about that. Luckily that was in a time when it was not so easy to find a writer. There were publishing houses and agents: worlds of protection in between the reader and the writer. But if I have one lesson to give young writers first publishing, it is this; don’t kill the dog.

Unless, of course, you really have to.