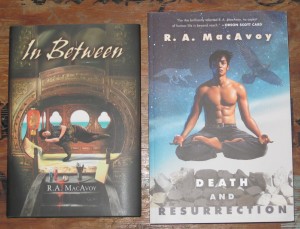

Note, once again, a book with two titles. This was by no means on purpose by me. In fact, I wasn’t aware for a long time that it had two titles. In-Between was the working title for the book, but I then chose the more ponderous title because the book has as one principal character a body-sniffing dog, such as are used by the police. These beings are astonishing creatures. There are some that can find bodies underwater, by sniffing the air above.

In the Pacific Northwest we had, at one time, such a dog and its name was Sorrow. Discovering that so moved me and impressed me that when I found I had a similar dog in the manuscript I was impelled to give her the name Resurrection. Hence the title. It is a pun, but not exactly a jolly one.

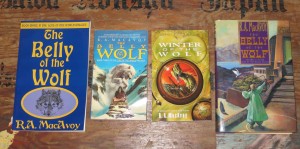

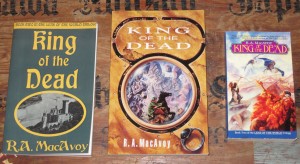

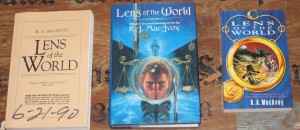

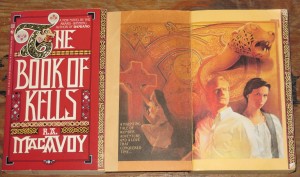

The other reason I didn’t fight harder to get the working title off the hardback copy (and I’m not certain my opinion would have mattered) is that it gives me the opportunity to have two gorgeous covers by Maurizio Manzieneri. I have a copy of the hardback cover – minus the print – framed in the central room of our shapeless and messy house. It is a treasure and the splendid man gave it to me. Just gave it to me.

D & R consists of four sections, each of which can stand alone. Almost. Any reader of Speculative Fiction becomes so very good at being dumped into media res that I’m sure it would not be difficult for them. But they build upon one another, and despite differences in narrative voice. For example the last of the four is more closely involved with the story of the female of the twins that are the protagonists of the book and it reflects her attitude about life more than do the others, which have the mind-set of Ewen Young, the brother of the two. He is more playful by nature. He is a painter and she a psychiatrist who works with children and with the dying.

There is a lot of dying going around in this book. It is probably a good idea that Ewen is light at heart.

D & R is definitely a fantasy story. There is none of the maybe it is magical and maybe it isn’t as there is in many others I’ve written. But as it is set in the present day in this world, I have tried to take into account the world as it is in the daily news. Or as I see it on the local streets, because it is set in my own neighborhood.

It also reflects the local reality that in the foothills outside of Seattle, and in Seattle itself, people of European ancestory are actually in the minority. They are certainly in a minority among my characters. I was very grateful to have that freedom, and tried no to tread on the toes of any of my character’s various cultural histories.

This one was fun to write, despite all the dying going on. It is the last one I will write using what is now being called The Legacy Houses. Places where a writer turned in a manuscript, got it edited and copy-edited and felt his or her job was done as long as the story made vague sense. And groused endlessly about the lack of understanding of editors and the idiocy of copy-editors.

What an arrogant thing I was. How much I have had to learn and am still beginning to learn. But that is taking me off-topic.